A group of Southern surfers chase a record-breaking swell as it lines up a remote reef break buried deep in the Catlins. What transpires has it all: blood, guts, an inhospitable peak and the rise of a new talent in big-wave surfing. New Zealand Surf Journal takes you inside one of the biggest days ever.

“There was nowhere for me to go – it was a direct hit,” explains Brad Roberts, who had been driving on a gravel road in the pre-dawn darkness through a tract of bush renowned for its free ranging wild deer.

“Somehow it survived the impact. I had no choice but to slit its throat with my knife right there on the side of the road.”

It is Brad’s first deer, which is something of a rite of passage for South Islanders. For years he’s hoped to go hunting for one, but never expected it to be like this. The left corner of his car is a crumpled mess, but it’s driveable. He loads the deer, a full-grown hind, into the foot channel of his jet-ski, wipes the blood from his hands in the dew-covered grass and continues on his way.

SIX HOURS EARLIER …

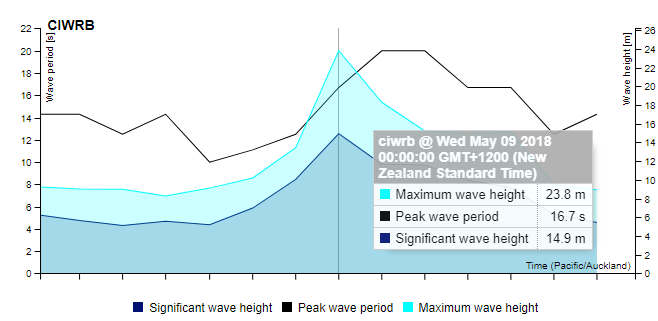

As the calendar clicked into May 9, 2018, a buoy located in the Southern Ocean off Campbell Island recorded a wave of 23.8m. It was just past midnight. Generated by a deep low lashing through the easterly passage beneath New Zealand, the wave was the largest ever recorded in the Southern Hemisphere. MetOcean Solutions senior oceanographer Dr Tom Durrant, who monitors the equipment, said even larger waves were created by this storm event as it moved north of the buoy. The buoy only records wave heights for 20 minutes every three hours.

PINPOINTING GIANTS

Days earlier an eclectic crew of surfers begin watching storms take shape deep in the Southern Ocean well below Stewart Island. One of those systems is something to get excited about. It has the ingredients for a standout session at a remote reefbreak located in the southern end of the South Island. Usually when this place breaks, it’s snowing sideways. Finding lulls in the wind is the only chance of scoring a decent ride without 1m-chop down a never-ending face. That hasn’t helped its popularity. Most people only surf it once, then never come back. Not this motley crew. They’ve hardened to its uninhabitable ways to the point where its nuances become just another part of the adventure.

Davy Wooffindin runs a building company in Dunedin with enough wriggle room built into his days to drop tools and give chase to the biggest swells. Nudging 40, he has a thick Irish accent with just enough drawl to offer a glimpse of the wave-crazed character lurking beneath. His tow partner, Nick Smart, takes the crazed element up another notch. He runs a surf school in the Catlins, manages some accommodation and incessantly plans his next mountain or surf adventure. Like many of them, he wishes the limelight never shone in the southern extremities of New Zealand and greets photographers with an acute scowl.

“This was the first big session of the year [it didn’t break last winter] and it didn’t have the wind that we normally get,” offers Davy. “That’s the thing with this place – you never know what you’re going to get, it’s always a gamble, always unpredictable.”

MORNING LIGHT

With the first light of day the visuals from our clifftop perch fill in to match the thunderous booms revealing what we all thought: the swell had peaked an hour before dark. It was forecast to drop below the reef’s threshold by early afternoon.

Davy and Nick waste no time and are first out. Back at the launch site, seasoned big wave surfer Leroy Rust and Wanaka-based surfer Malachi Templeton are hanging the deer, gutting it and wrapping it to keep the flies off.

“I’m not a hunter, but we lived in Norway and had a farm there so I knew how to butcher a sheep for the freezer,” offers Malachi. “We didn’t want to see it go to waste and Leroy hunts a bit and so he took the lead.”

Malachi, 35, describes his job as a skydive instructor as “a glorified bus driver”. But he’s playing down his feats. He’s talented at paragliding and speedflying, and tests for Ozone. He once flew more than 100km from Wanaka to Omarama in one day.

“The consequences of getting caught out and having to land somewhere two days’ walk from anywhere is very real,” he explains.

And that element of adventure is what drew him to big wave surfing in the beginning.

“I like to do stuff that’s a bit more of an adventure and living in Wanaka you get so wave-hungry,” he said of his mountain-encircled home town. “So, I bought the ski about 18-months ago and started chasing big waves. The camaraderie being out there with someone else and trusting in the team you’re in the water with – you put your life in their hands and they do the same for you. You don’t need to catch a million waves to get the buzz.”

For Leroy, that buzz isn’t on the end of a rope. He’s one of a small crew who have been paddling here for years. Together with close mates Jimi Crooks and Tom Bracegirdle, and the older guard of Taane Tokona and Oscar Smith, they’ve stroked into the biggest waves of anyone out here. Today Leroy has a Graham Carse-shaped 10’ Quarry Beach gun that has been made just for this wave.

For the past four years Joe van der Geest has been training for big wave surfing. Better known as Joe Dirt, he now sits nervously with his Roger Hall designed, Homa Mattingly finished 10’2” Seer board the way you would when you’re about to head solo into an arena with a lion for the very first time. Another surfboard shaper, Steve Brown, has joined the fracas from Timaru hoping to etch a couple of indelible memories into his own mind. Joining them is one of New Zealand’s most prodigiously talented barrel riders, Jamie Civil, who is here “just for a look”. It’s his 32nd birthday and he’s driving one of the safety skis. Jamie Richards and James Cross are on the other safety skis and I have big wave surfer Dave Wild driving for me.

The route out to the line-up is a maze of ridges and valleys, catching glimpses of the buckled horizon on the peaks and losing sight altogether in the troughs. Kelp, ripped from its anchor by the storm, lies in thick bands waiting to be sucked into an intake to render the skis powerless. Two skis are forced to fall back to clear impellers.

Dave has chalked up more than 1000 hours on a ski in the ocean and tells me “when you see a gap, you just gotta go”.

We’re the second ski to make it out and can tell that Nick and Davy have had some eye-opening rides already. They play it down.

“Not as big as it gets, but the odd nice one coming through,” they share.

The estimates are meaningless out here when you have an oversized arena like this, but Nick calls it 12-15 foot with the odd 20-footer. That’s in the range for the paddlers who are nervously checking their equipment, studying the take-off zone in intricate detail and running through their pre-surf rituals. The rule out here is that once the paddlers hit the water the tow-ins stop and give them space.

For roofing contractor Joe, this is what the past four years have been about.

“It was phenomenal – I put all my faith in Leroy and just listened to everything he said,” admits Joe.

Eighteen months ago Joe’s big-wave dreams got derailed when he suffered a head injury surfing at Blackhead in Dunedin.

“It was the fittest I had ever been,” he shares, recalling the day the board cracked him in the temple. “It took about 18 months to come out of it – constant headaches from the concussion.”

“It’s made my desire to surf these big waves even stronger – I feel like I’ve been robbed a couple of years so I am keen to make it up,” he laughs.

We watch the peak – an impossibly hollow take-off that shuts down into the next section, then walls up again and, if you’re lucky, gives you a perfect ramp into the inside bowl – itself a heaving section that reels right in front of the rocky cliff face. It’s the ultimate if you can make a wave through here, but fall just short and there is no forgiveness.

The horizon buckles again and Brad appears as a dot way out wide on a monster set. He rides it through the first section as it rears up behind him larger than anything we’d previously seen. The channel erupts in a cheer. The paddlers shift nervously on their skis.

“It felt a lot bigger than a lot of the other waves,” offers Brad who works as a plumber and drainlayer in Curio Bay at the southern end of the Catlins. “When you’re riding those things you’re not really taking the size into account, you’re so focused on what’s in front of you. You’re going so fast and if that lip lands behind you it will mow you down and take you out. Even if you’re going at full-speed this wave is always moving faster. I got through by the skin of my teeth on that one.”

The 35-year-old has surfed this wave more than most.

“On a day like this you want the big ones,” he chuckles heartily. “That’s the whole reason I do it – to ride the biggest wave I can.”

A few more bombs roll through much larger than the standard canvas on offer. Davy is in his element throwing big carving bottom turns and top turns into the mix.

“As long as you stay in the top two-thirds of this wave you’ll be okay,” he later tells me.

Even so, the speed he wipes off in the turns gives the wave a chance to catch up with him and he is engulfed several times.

An even bigger wave comes through and the dot sliding down its face is Jamie. It’s his first time on a wave of this size, which makes his next move even more surprising. Instead of angling down the line, he fades out to the flats before laying in to his bottom turn. Ordinarily this is a beautiful way to surf, but with a line-up of this scale it’s nearly always going to be rewarded with a full-rinse that will take you to a very dark place. True to form the lip zeroes in on Jamie and gives him the full South Pacific Ocean initiation. A birthday present that he’ll never forget. Ever.

The paddlers look uncomfortable. Bigger sets are breaking outside the usual take-off spot putting the prospect of paddling into one somewhere between foolish and reckless.

“I was waiting for Leroy to make the call,” admitted Joe afterward. “He’s the most experienced paddler out there. But the arena was solid and with the big sets it would have been a dangerous scramble.”

For 28-year-old Joe the bigger sets are the cue he needs to jump on the rope and hunt one down with the ski to flick him in. He probably didn’t expect to get one of the waves of the day, but that is exactly how he debuts at this spot. Dropping and fading into one of the biggest waves of the session and, following Jamie’s lead, beyond the point of return with his line choice. The detonation is frightening.

“My mind went super clear – nothing was running through my head, on that drop,” Joe reveals. “I can hardly remember the wave because of the adrenaline. I took my natural line and got to the bottom and went to turn like on a normal wave. I didn’t even look up to see how big it was. It all happened so quick.”

He never saw the impact looming behind him.

“I didn’t see the lip coming down,” he laughs. “I can’t remember the working, but I know it was the biggest of my life. It wasn’t until I saw the picture that I felt scared.”

Not long after Joe’s bomb, the swell abates. By midday the line-up is barely breaking. We return to the staging area and breathe that collective sigh of relief that we’ve all made it back safely. Hanging in the tree is Brad’s deer, slowly being cut up with its venison being distributed among the crew. Brad gets the backstraps. Every part of the animal is used and shared, a fitting end to a day hunting wild peaks on one of those rare days when the stars align. Unless you were the deer.