Most of the kaumatua of New Zealand surfing will tell you that they’ve forgotten more than we’ll ever know. Assembled around a campfire in the post-surf glow of twilight the stories tumble out like moths attracted to the flames. These are stories that should be treasured, told and re-told. Like the time Kim Westerskov ran into one of the surfing world’s greats …

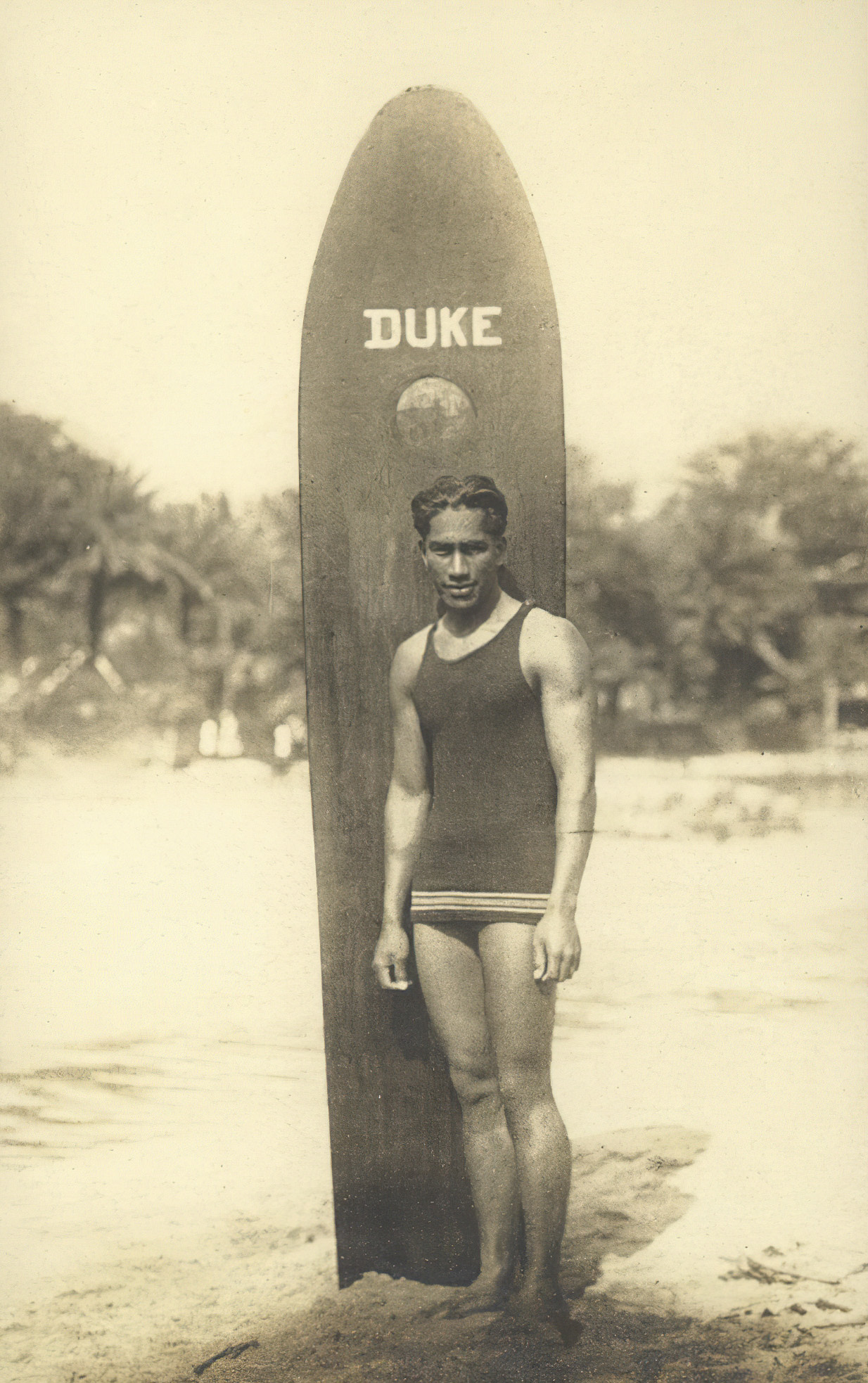

Duke Kahanamoku was the father of modern surfing. In his prime, he was also the world’s fastest swimmer. The tall Hawaiian broke several world swimming records, sometimes by so much that officialdom reacted with, “that can’t be true. The buoys must have drifted, or there was a current – or something! We can’t allow that record to stand”. Beating the world freestyle record for the 100 yards (91 metres) by 4.6 seconds certainly raised eyebrows. His feats were eventually recognized by USA’s Amateur Athletic Union many years later. He won five Olympic swimming medals: three gold, and two silver.

He was a superb swimmer, surfer, and all-round waterman, but he was many other things as well, including part-time film actor and Sheriff of Honolulu for nearly 30 years. He even taught the Queen Mother how to dance the hula.

“Duke” was his given name and not a title, this likable, humble man never stopped telling people. He was a tireless ambassador for Hawaii and the Aloha of Hawaii. Aloha is a word found in all Polynesian languages, always with the same basic meaning of love, compassion, kindness – and also sympathy, gratitude, mercy, peace, even grief. Aloha is often used as a simple greeting, but for Hawaiians, Aloha also has deeper cultural and spiritual significance, being the very force that holds existence together.

During the dreary, grey years of World War One, he toured Australia and New Zealand, bringing welcome Hawaiian Aloha. In both countries, he demonstrated to many thousands his swimming skills and introduced them to the joys of surfboard riding.

In 1915 he gave well-attended demonstrations at New Brighton Beach in Christchurch and Lyall Bay in Wellington, plus a third at Muriwai Beach near Auckland (about which much less is known).

Surfboards at the time and for some decades after were made of solid wood: big and heavy and though surfing definitely “got going” after Kahanamoku’s visits, the numbers following this new sport were never big.

That changed forever in the late 1950s and early 1960s when surfing exploded onto the scene in many countries: shorter, lighter boards (first brought to New Zealand by two American lifeguards in 1958), surf films including Bruce Brown’s The Endless Summer, surf music (the Beach Boys, Surfaris, Dick Dale) and a generation of teenage baby boomers looking for freedom, adventure, and excitement.

In July 1961, I travelled with my parents and sisters to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. My father, an academic, had arranged a year’s sabbatical leave at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. I was a teenager at the time, though only just – 13. Memories include Canada being a BIG country with seemingly endless outdoors – as an outdoor sort of guy that suited me just fine – deep snows in winter, temperatures dropping to minus 40°C, and hosing down our backyard to create a small ice skating rink.

Twelve months later we headed back to New Zealand, taking a train through the spectacular Canadian Rockies to Vancouver. The Canadian border with the USA was just a stone’s throw away, so we crossed it briefly so we could say we’d been in the USA.

For reasons long forgotten our whole family ended up inside the building at the border post. No big deal, as far as I remember, probably just formalities. A photo of President John F. Kennedy hung on the wall. “Do you know who that is?” a friendly border control guy asked my sisters. “Elvis”, replied my older sister promptly. Some things you don’t forget.

A photo of President John F. Kennedy hung on the wall. “Do you know who that is?” a friendly border control guy asked my sisters. “Elvis”, replied my older sister promptly. Some things you don’t forget.

So what’s this Canada trip got to do with surfing? Nothing much yet, but hang on, it’s coming.

We had travelled to Canada on the P&O Line’s SS Canberra, a state-of-the-art ocean liner launched just a few months earlier, but we were flying back. Vancouver to Hawaii, then Hawaii to New Zealand.

Our plane touched down in Hawaii. We’d hoped to spend some time there, so were disappointed to hear that – because of scheduled atom bomb testing about to start – we were to board our New Zealand flight just a few hours later, in the middle of the night.

A brief digression: My father had been active in the Danish resistance during World War Two in German-occupied Denmark and was made of stern stuff. Danish railways were important for Germans transporting men and supplies to and from Norway and the Danish resistance made over 2000 attacks on the railway network, blowing up railway lines and bridges. This did not go down well with the Germans and many of his fellow resistance fighters were captured by the Gestapo, including his close friend Villy who, in my father’s exact words “was terribly mistreated by Gestapo”.

My father escaped by the skin of his teeth to Sweden, helped by some good luck, taking with him a map of a German military airfield about to be constructed for an attack on England, which never came. The map and other military information he’d gathered was promptly passed on. In Sweden, he joined the Danish Brigade under the command of the 8th British Army, undertook some hard commando training, and landed with the Danish Brigade back in Denmark on May 5, 1945. So, no, my father wasn’t the kind of person to be pushed around by airlines and he convinced – more likely, “told” – the airline to put our family up in a hotel on Waikiki Beach until the test or tests were over. Much better.

I don’t remember much about the hotel, apart from the endless and free pineapple juice. But it was right on the beach. Waikiki Beach. Where people surfed out there on the reef a bit offshore. Something flammable caught alight (figuratively speaking) in my now all-grown-up 14-year-old mind.

I’ve never been the kind of outgoing person who wanders up to strangers and starts conversations, so I don’t remember talking to anyone on Waikiki Beach – apart from one man. Presumably, I was standing there looking out to sea and looking somewhat wet behind the ears, something I was probably pretty good at, but alive to possibilities, when a tall Hawaiian man walked past, paused, turned and greeted me. We got talking.

Duke Kahanamoku was in his twilight years. He’d given up surfboard riding a few years previously, though he still swam and sailed. He’d also recently lost his – largely ceremonial – position as Sheriff of Honolulu when Hawaii became a state of the USA in 1959, a position he’d held since 1932.

I don’t know what he saw in me or what made him do it, but it changed my life. We chatted some more, I missed dinner back at the hotel. He invited me to meet him again on the beach the next day. “Bring your swimming trunks”.

The next day was a turning point in my life. Not everyone can say they were taught to surf by Duke Kahanamoku. Surfing: I loved it instantly. All of it. The freedom, the caress of the sea, the rush that every surfer knows as they are propelled shoreward with no assistance, but the joyful dance between the laws of oceanography, physics, and adventure.

The next day was a turning point in my life. Not everyone can say they were taught to surf by Duke Kahanamoku. Surfing: I loved it instantly. All of it. The freedom, the caress of the sea, the rush that every surfer knows as they are propelled shoreward with no assistance, but the joyful dance between the laws of oceanography, physics, and adventure.

Duke rode many boards over the years, from his huge 16-foot-long, 114-pound Koa wood Olo board to ones half that size, of many designs and constructions, with fins –rarely – and without. He was always changing and adapting his boards. Fortunately, the board he taught me on was one of his shorter boards, and light enough that I could lift it by myself … just.

It might be worth mentioning here, especially if you are looking at photos of him riding small waves, that he was equally comfortable in big surf. In 1917 he caught a huge wave on the outer reef at Castles near the shipping lanes and rode it for a mile to Waikiki Beach. He achieved this by linking several surf breaks: Castles, Publics, Cunha’s, Queens, and possibly as far as Canoes. There is some uncertainty about where the ride ended. What is not in doubt is that this feat required exceptional skill, stamina, and guts. Duke Kahanamoku’s ride instantly became the stuff of legend. How big was the wave? Kahanamoku said it could have been 30 feet. On a 16-foot-long, 114-pound redwood board without a fin! A “thirty-foot” wave to a Hawaiian would probably be a 40 or 50-foot wave to many other people.

All too soon it was time for our flight from Honolulu back to New Zealand. Much to my surprise, Kahanamoku offered me an old board of his, but presumably surplus to requirements. Or perhaps it was simply Kahanamoku’s big-hearted generosity. Of all that I’ve read about Kahanamoku since those few idyllic days, I don’t remember reading a single bad word about him. Everyone loved him, seemingly, with his big smile, engaging manner, and a heart full of Aloha. A remarkable achievement for someone known worldwide. And perhaps most importantly of all, he remained true to himself and to the Hawaiian Aloha.

My parents were very surprised when I lugged a big, wet surfboard into our carpeted hotel room. So were the airport staff. Kids, and I was still a kid, simply didn’t travel to New Zealand with wooden Hawaiian surfboards in 1962. Anyhow, the airport people were kindly – some looked like they might be surfers themselves – and allowed us to travel with considerably more baggage, weight-wise, than what our tickets normally allowed.

The story now jumps ahead several months to summer. A Dunedin summer.

Otago’s Murdering Beach is one of our premier surf breaks. Forty minute’s drive north of Dunedin, Murdering offers long quality rights on a good day when a solid northeast swell wraps around the point. On a big swell, rides can be up to 600 metres.

Before 1998 we called it Murdering Beach, its official name since the first surveying map in 1863. In 1998 it became Whareakeake, its original Maori name which was restored as part of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act. Surfers nowadays often call it Murdering or Murderers still.

I got to know the farmer at Murdering Beach and spent as much time there as I could. I even lived a while in one of the caves near the beach. It was big and dry with a nice flat floor. Plenty of room for a cooking fire, somewhere to sleep, and my board. And close to that magic surf, though – facing north – it was dead flat whenever the normal southerly swells were pounding the outer coast. But in a northerly or easterly swell, it pumped and was magical.

The biggest waves I ever rode at Murdering were actually the very first time – 14 December 1962. It was only later that I realised how lucky I’d been to strike it that big on my first visit. I took a quick photo and made my way down the track – there was no road back then. I only got three rides that day, but I’ll remember those three waves for the rest of my life. All the way from out way beyond the point to the beach. By myself. With only the seagulls and early summer sun for company. Magic.

I’ve always been a photographer, so yes, I did take some photos of the board, but I’m blowed if I can find them here amongst what I fancifully call “the archives” – the piles of stuff in the next room, or the other room, or in the other office maybe.

And where is Duke’s board now? It was big and heavy and I did not have my own car at the time, so getting the board and me to Murdering was quite a mission in the first place. Once there, I just left it in the darkness at the back of one of the more remote caves at Murdering. It seemed a safe enough thing to do. Even as a student living in Dunedin from 1970 to the early 1980s, none of us ever locked the back door. Then, one sad day my Duke Kahanamoku board was gone. I never found who had taken it or what happened to it. One of life’s mysteries, in this case, a rather sad one.

I know there are several Dunedin surfers – hello to Cog (John Leslie), Brian Muntz, Julian Allpress – who think they might have been the first to surf Murdering, but unless they were there before 14 December 1962 then it might just have been me who was first to ride those magical waves. Not bad for a 15-year old wet-behind-the-ears kid, eh?