Finding new waves on planet earth these days is a pretty tough ask. Sure the odd slab might be unearthed here and there, but the goalposts are well out on any significant discoveries. Especially here in New Zealand. So when I was given the chance to join an expedition voyage to the Subantarctic Islands in December my curiosity was bouncing off the rev limiter. Nearly 1200 nautical miles later and we have some exciting discoveries. Here’s Part 1 and our Campbell Island assessment.

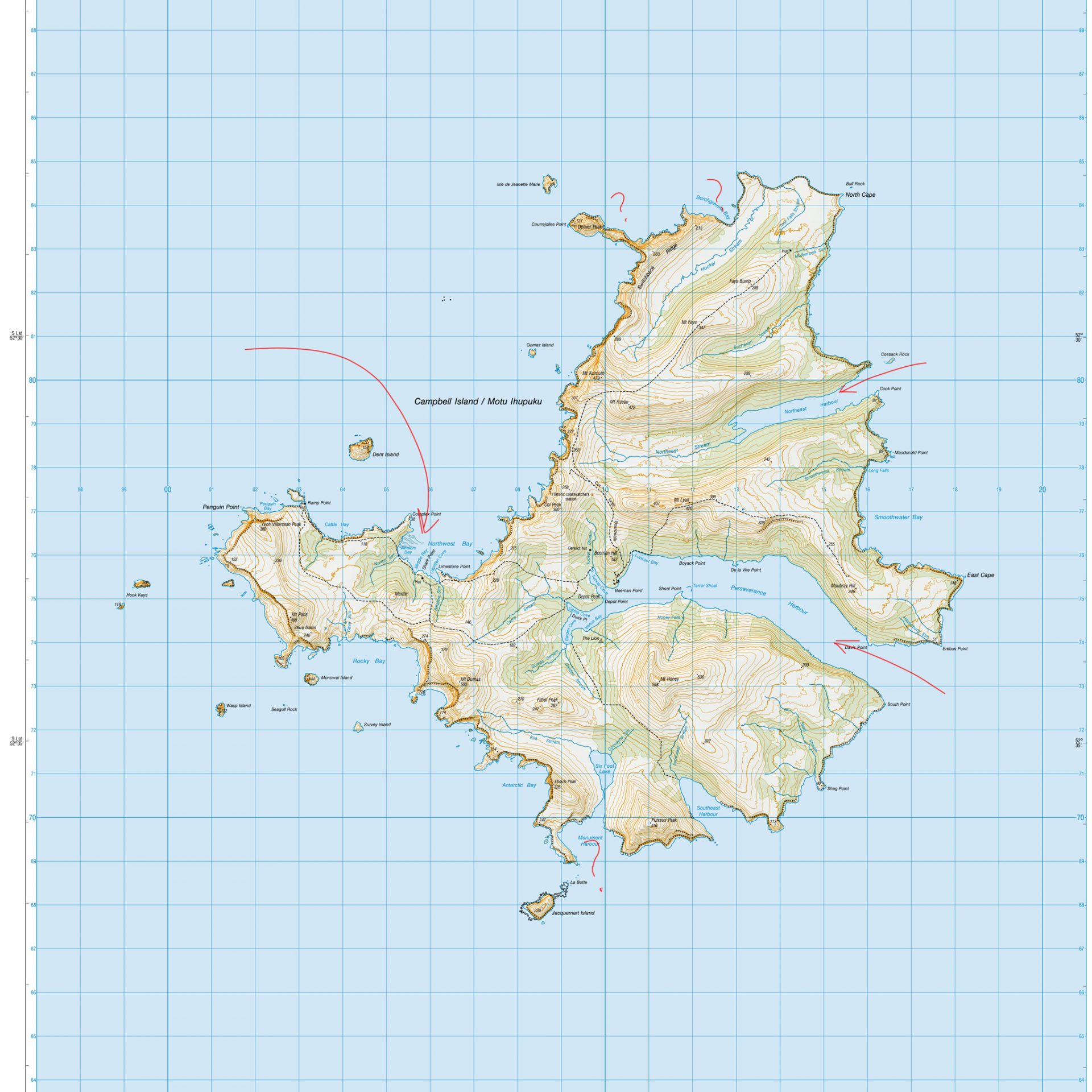

Campbell Island lies 700km almost directly south of Bluff at a latitude of 52° 33′ S – smack bang in the Furious Fifties that define the Southern Ocean. At 11,331 ha Campbell Island is the second largest of the five Subantarctic Island groups. The island was first discovered by Europeans in 1810 and became a reserve in 1954 – Campbell Island along with the other four island groups in the Subantarctic: The Snares, Bounty Island, Antipodes Island and Auckland Islands, receive the highest form of protection from New Zealand in recognition of their value. They are national nature reserves. In 1998 the five island groups were listed as a World Heritage Area in recognition of their “outstanding universal value and superlative natural phenomena”. That puts them on par with the Grand Canyon and the Great Barrier Reef. The World Heritage nomination described the islands as “havens of endemism”. In 2014 Campbell Island also became a marine reserve.

I’m travelling with Heritage Expeditions aboard the Spirit of Enderby, aka Professor Khromov. It’s a 75m long icebreaker research ship that’s been converted for ecotourism operations and expedition cruising. The crew are Russian – they came with the ship lease and manage everything on the ship under the guidance of Captain Dmitry Zinchenko. He’s a man of few words. The expedition crew are a mixture of Kiwis and internationals under the guidance of expedition leader Aaron Russ. Most of them have a science background and many of them have studied the flora and or fauna in this part of the world. Aaron, and his brother Nathan, bought the company from their father Rodney in winter of 2018. Aaron grew up in a world of expeditions and science. He has led expeditions and guided throughout the world.

Aaron seems a bit puzzled by my unwavering need to find some waves during the voyage. My board and dive gear is stored in the wet room near the crane that lifts the zodiacs into the water. I have no idea if I’ll find waves on Campbell island, but I have good intel that there are some promising setups on the north east edge of the Auckland Islands. Aaron shakes his head and explains that he is not sure if he’s ever seen rideable waves in the subs.

We arrive in Perseverance Harbour on Campbell Island in the pre-dawn light after 36 hours of 11 knot travel through impossibly calm seas. It seems a long way from the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties we’d been braced for. The harbour is dead calm. The sun is pushing its way through for one of the 40 days it shows its face each year according to the island’s weather records. To the north Mt Lyall cuts an imposing ridge across the horizon and the tallest peak on the island Mt Honey (569m) dominates the southern edge of the harbour.

Our plan for the day is to explore the harbour by zodiac and then climb to Lyall Col (250m) in the afternoon.

The island is the eroded remains of a 6-11-million-year-old shield volcano and sits on the southern edge of the Campbell Plateau. Its more sheltered eastern edge is cut away with four harbours and various bays and inlets with evidence that glaciers may have once filled these valleys. Our zodiac cruise reveals a healthy population of New Zealand sea lions inhabiting Perseverance Harbour with the biggest males reigning over their harems and the less skilled males outcast to develop the necessary strength, savvy and charm to take on the beachmasters. We meet a few of the outcasts and they look suitably disgruntled.

Most of the eastern edge of Campbell Island features bluffed out coastline with little promise for waves. The harbour mouths are lacking any type of graduated profile that might hint at a wave. Even with the highly unusual 2m northeast swell, very little swell is getting into the harbour itself. If a swell did happen to line up properly, then Perseverance, Southeast and Northeast Harbour might spring to life with an inner harbour wall. But you might be waiting a very long time.

On the bigger and more prevalent southern and souwest swells it is possible that swell might wrap into Monument Harbour, steered in and focused by the satellite island Jacquemart. The options are certainly limited on the friendlier and more accessible eastern side.

In the afternoon we head through fields of flowering megaherbs and climb through to Lyall Col. From the saddle to the peak we’re met by nesting Southern Royal Albatross – gigantic birds that look at us with puzzlement. Some clack at us in disgust. Others just watch us walk past – sometimes as close as a few feet away without concern. It feels like we’re walking through the set of a David Attenborough feature.

We reach the ridge and can’t help but smile as giant Southern Royal Albatross assume a place in a landing pattern and plummet ungainly towards the megaherb runway. Touch down is never graceful, but these creatures make up for it when they meet up in groups like a bunch of mates talking up the day’s events at a local bar. I could never get bored watching their antics. The ridgeline offers expansive views into Northwest Bay – a semi protected bay thanks to Dent Island standing sentinel off Ramp Point. A small 2m southwest swell is running and every 20 minutes a wave breaks along the inside of Complex Point. It’s a lefthander and looks like a sand-bottomed point feathering into Whaler’s Bay. It’s offshore in the stiff westerly and looks promising. I’m about 3km away, but can see potential for beach breaks at Middle Bay and Capstan Cove before the limestone cliffs rise above the bay to the north. I can’t quite see around to Cattle Bay, but my guess is it would be too exposed to the raw swell to offer much promise.

Further north the coastline is weatherbeaten and raw – exposed directly to the ferocity of the southern ocean. The 2km long Courrejolles Point might be the most promising feature along here – the North Cape is a cliff-fringed coastline with very little relief. Further south Rocky Bay and Antarctic Bay bare the full brunt of the southerlies, but I suspect on their day, and in the rare breath of a northerly, might have enough interesting topography to produce something worthy … maybe even something to rival Cyclops. Like all great discovery that “what if” is what keeps us moving forward.

On the ship that night I chat with the expedition crew about my thoughts on Northwest Bay having the best wave potential of all on Campbell Island. Their glances dart around and then one of them volunteers the story of Mike Fraser.

Campbell Island has long been used as a meteorological station and often had a team of workers stationed there to make weather observations from the Southern Ocean.

On April 24, 1992, Mike Fraser was leading a Metservice team when the four of them decided to take a break and go for a swim at Middle Bay – the centre bay in the Northwest Bay trilogy. Mike, 32 at the time, was snorkeling in the bay and was about to come in when he felt a big hit from the right and was pulled under water. He instantly thought a sea lion was having a play with him, but looked down to see his right arm in a great white shark’s mouth. He broke the surface briefly before the 4m-long shark pulled him down again, this time taking his arm completely off and lacerating his left in the process.

With the team looking on in horror, Mike began to kick back to shore. Despite the risk of a further attack he was met 30m out from shore by Jacinda Amey, who was then 23. She pulled him to the safety of the shoreline and assessed his injuries with the rest of the team. He had lost his right forearm and his left forearm was lacerated and appeared broken. Mike was in intense pain, losing blood fast and was in shock. The team managed to contact authorities in New Zealand where Taupo-based helicopter pilot John Funnell opted to lead the rescue. He would fly his Squirrel the 700km from Invercargill to Campbell Island via a fuel dump at Enderby Island in the north end of the Auckland Island group. They left Invercargill in the dark of night.

Mike’s wounds were attended to by his team as best they were able as he lay and wait. They administered shots of pethidine to stave off the pain and talked him through the night. John and his co-pilot Grant Biel arrived with fresh blood supplies at dawn. Mike was bundled in and flown to Invercargill Hospital.

Mike survived the ordeal thanks to the heroic actions of Jacinda Amey, who was awarded the New Zealand Cross – the highest bravery award – for her actions. Pilot John Funnell was also recognised for his actions flying across more than 1300km of ocean in a single engine helicopter – a feat that was believed to have been unprecedented anywhere in the world.

The attack is considered to be a classic great white encounter (species confirmed by a tooth extracted from Mike’s arm) in that the shark didn’t pursue the victim after the first bite.

Sharks aside, there are a few other elements to deal with on Campbell Island – it rains 325 days of the year and has a mean air temperature of around 6°C. Add in the wind chill that will almost certainly be a factor and we’re talking seriously cold. Campbell Island cops hurricane force westerlies at times. The water temperature is the coldest in New Zealand hovering at around 8°C on average. Because of its level of protection a permit is required to land on Campbell Island, which is administered by the Department of Conservation in New Zealand.

Campbell Island is no place for the faint-hearted surfer. A mission here takes some serious logistics and requires a great deal of luck to strike the right set of conditions to turn Complex Point into something special from the maelstrom of life in the Furious Fifties on the edge of the Subtropical Convergence. Good luck.

NEXT: Auckland Islands journey reveals a host of line-ups on Enderby Island.