I’m standing in the garage with him as he sniffles back the taps and shuffles through a rack full of surfboards, his long hair hanging flat. He pulls one after another out and they’ve all got stories: he’s made a bunch of them, rode others to world titles and has been gifted others from people like Adriano De Souza and Michael Peterson.

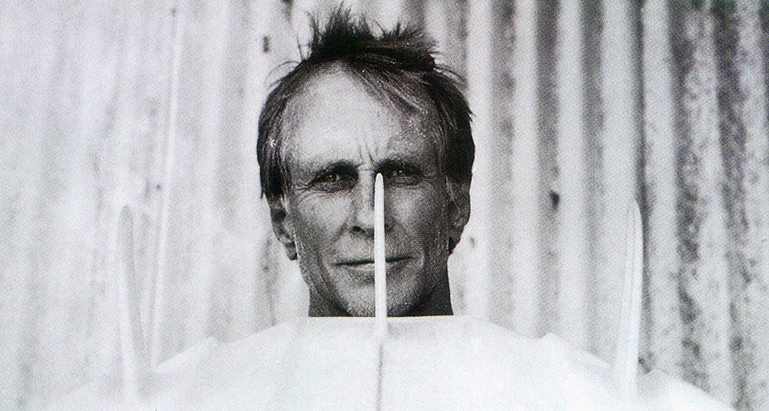

He’s one of the most humble surfers I’ve met and in many ways the most successful surfer ever to come out of New Zealand. But I never knew all of that.

His story has blown me away and I wonder why he hasn’t been higher on my radar. Right about that point he turns to face me, tears welling in his eyes and in his next few sentences Ratso, who turned 59 in March, reminds me why our past is so important to our future, why it has to be celebrated and championed.

He’s not shedding tears for his own omission from modern surf journalism in New Zealand, but that of the late Allan Byrne.

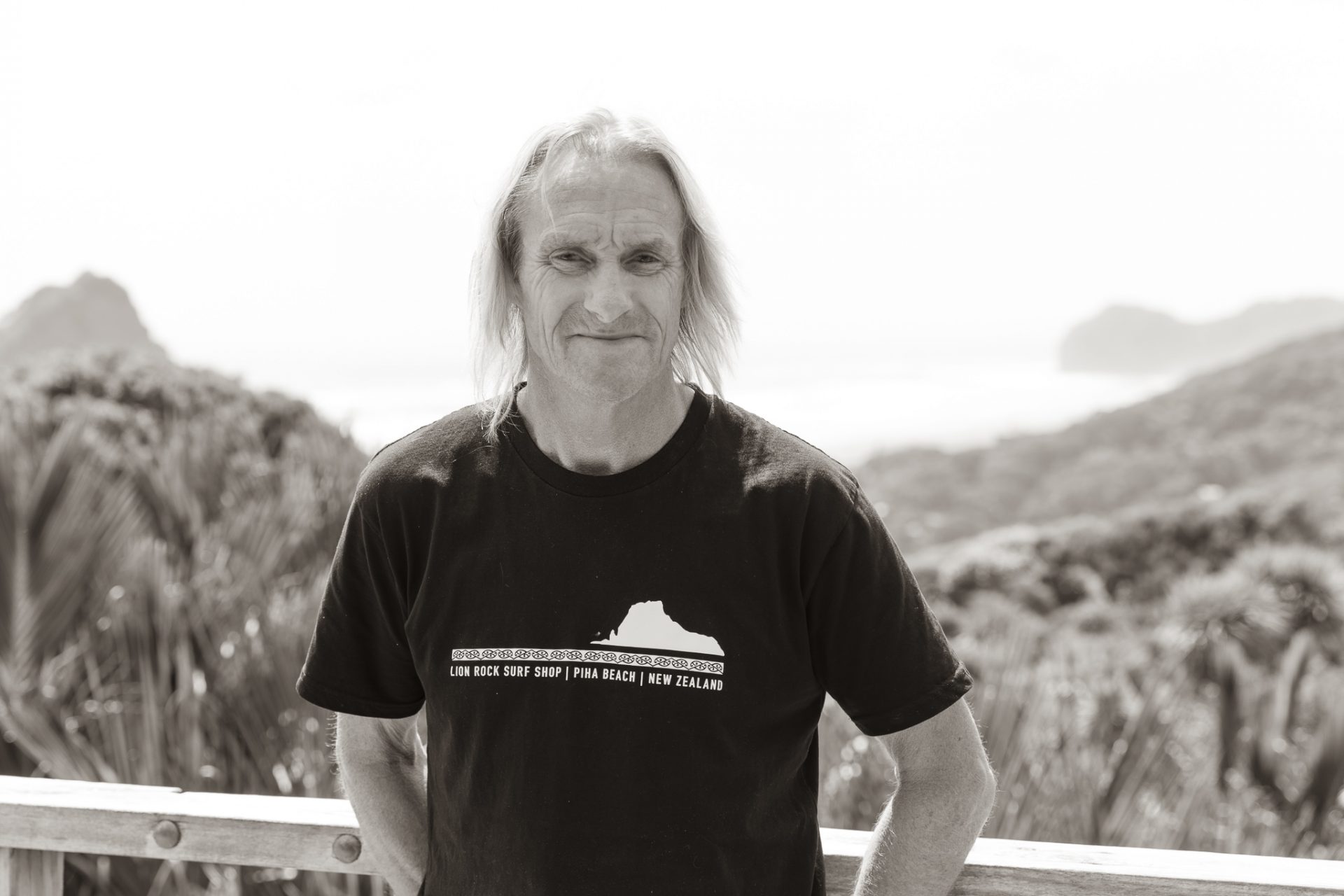

I meet Iain Buchanan, or Ratso as he is better known, at his home base in Piha – “Garry’s place” perched in the bushclad hills above Lion Rock. He spent the previous evening at a heaving Pennywise concert in Auckland and is watching eagerly for the wind to swing into a favourable aspect for a sneaky wave or two.

Strangely, I’m nervous to meet him. He’s existed in the shadows of my surfing exposure for more than 30 years, but we’d never crossed paths.

Ratso has recently returned from the World Surf League (WSL) finale in Hawaii and so we start there with a couple of Steinlagers he’s pulled from his fridge.

“Billy [Stairmand] surfed strongly at Sunset – he was on a mission,” he tells me, revealing his pride in the Kiwis. “He’s definitely got a new zest this past year. It’s a tricky spot to surf – you have to be in the right position to line up – even getting a wave is hard.”

“You can go out there for a two-hour surf and you only get three waves sometimes,” he shakes his head. “You’re always dodging sets and they ride such small boards, too, those guys.”

He tells me Billy did well in Hawaii, but admits it was a tough season for Ricardo Christie.

“I talk with him a lot – he always surfs strongly in Hawaii, but through the middle of the year if you’re not bringing your A game, then you get exposed a little bit,” he admits. “It seems like he used to do a lot more airs when he was younger. He needs to bring that back – things like that – it’s just better to mix it up.”

Ratso is the priority head judge for the WSL. It’s a pressure cooker role that he loves. It also gives him a front row insight into the world of the WSL. He’s earned his stripes to get there.

Ratso won five national surfing championships in a row from 1983 to 1987, equaling the dominant record form shown by Wayne Parkes from 1966 to 1970. It’s a record that few have been able to come close to … until Billy Stairmand had his shot in 2018 after taking victory from 2014 to 2017. Billy’s good mate Ricardo Christie ended his chance at equaling five on the trot.

“I was pretty stoked that Billy didn’t win that one. I’ve still got that record – well, I share it with Parkesy, but it’s good to still have that record 30 years on.”

“I was pretty stoked that Billy didn’t win that one,” smiles Ratso. “I’ve still got that record – well, I share it with Parkesy, but it’s good to still have that record 30 years on.”

While he didn’t get the consecutive record, Billy has the record for most male national championships with seven engravings on the iconic mug.

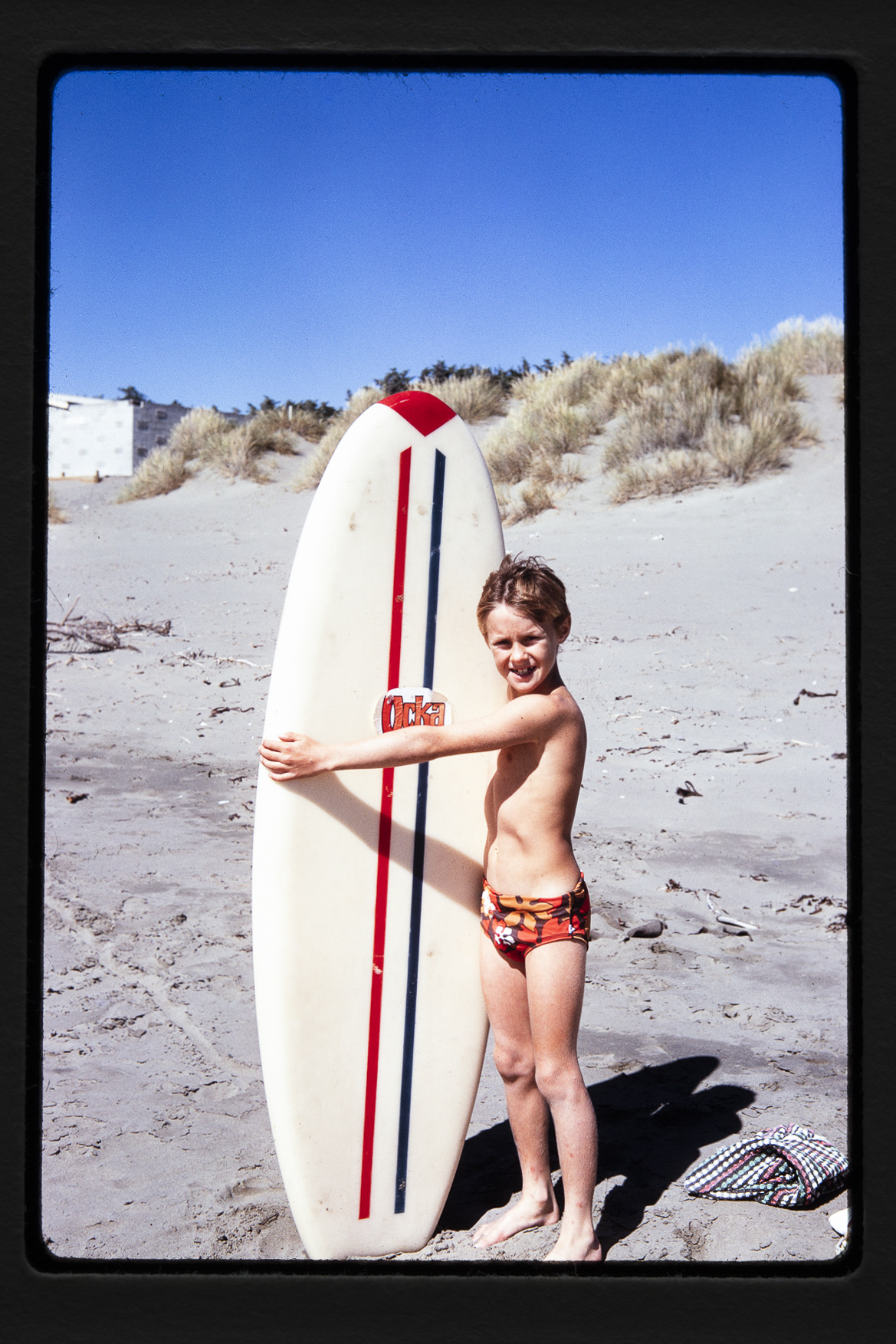

Photo: Ratso Archives

Ratso was born in Christchurch and started his early years in St Albans – about 8km from the beach at New Brighton. He learnt to surf through “one of my sister’s boyfriends”.

“I’d tag along and learnt to surf with him,” he recalls. “I used to surf New Brighton and just down from North Beach at the end of the road at Waimairi Beach. They’re not the greatest waves to learn on and it’s pretty bloody cold. We didn’t have wetsuits for our sizes like the kids have these days. We used to go to the dive shop and buy sheets of rubber and make our own booties and gloves. We used to buy Ados glue, glue them up and stitch them up. We used to wear rugby jerseys in the water and we’d think they’re keeping us warm – it was pretty tough. Not like the kids have got these days.”

Surfing struck a chord with Ratso and by 16 he decided to move to Australia to live with some friends in Maroochydore.

“Then I went down to Sydney and then, just for three weeks, I went down to South Australia where my sister was living,” he explains. “Down to a place called Port Lincoln – quite a way from Adelaide. It was really hot and there was not much employment there. It was hard to get a job – it’s a big tuna fishing town so the guys that were on the boats made a lot of money.”

Ratso said the South Australian waves were unreal.

“I remember hitching to Cactus with another guy and we spent 12 days there,” he tells me. “We surfed Blackfellows at Elliston and Streaky Bay and Granites. I don’t think I’d go back there and surf again knowing how dangerous it is with the sharks there. I was just young and dumb back then. Elliston was a pretty unreal lefthander – you do down this big sandhill and paddle out to this reef and you’re out in the middle of nowhere. You flick off a wave and it’s like deep blue, you know, it was so scary. We thought about the sharks a little bit, but didn’t really know how bad it was. There was actually a Kiwi guy I knew who got taken at Cactus and then the next day or two days later, a boogieboarder was taken at that Blackfellows place – within days. There are just so many sharks there.”

“There was actually a Kiwi guy I knew who got taken at Cactus and then the next day or two days later, a boogieboarder was taken at that Blackfellows place – within days. There are just so many sharks there.”

Luckily, Ratso didn’t see any himself but a few times when he surfed a right point at Fisheries Bay in Port Lincoln he’d get out of the water because sharks were spotted.

“I spent nearly a year there just surfing and I wrote to all these different surf factories around the place and tried to get work,” he recalls. “Then G&S Surfboards in Cronulla offered me a job and so I ended up back in Sydney.”

Ratso took the job in the summer of 1978-79 and described his role as being “like the factory rat at the bottom of the chain”. But that’s not how he got his nickname.

“We used to play a lot of touch rugby in between surfs at Cronulla,” he tells me. “They said that when I ran with the ball I looked like a rat, because I always had long hair. That’s how it started – playing rugby with my surfing mates there. Everyone in Australia has got a nickname – it’s always Davo, or Stevo, or Wayno … names like that. So that’s, how Ratso came about.”

In 1982 the New Zealand Surfing Circuit forms and attracts Ratso’s attention. He starts to return to New Zealand to compete.

“Terry Fitzgerald was coming over to set-up Hot Buttered and to look around,” Ratso recalls. “He saw me at a contest and offered me a deal. Part of the sponsorship was that I could work for him shaping. So I ended up changing to Hot Buttered. I was living in Cronulla, which is the southernmost suburb of Sydney and then I was working at Narrabeen on the north side. So it was quite a mission driving over there each day. I managed to do a deal where I could bring blanks back and shape boards in another shaping bay in Cronulla and then take them back at the end of the week.”

Ratso worked for Terry for 12 years. He learned a lot and met a lot of people, too.

“The connections I’ve got today are from on the north side,” he reveals. “I met a lot of people, it was really good for my career. And to be taught by him was unreal. Greg Webber was working there – he was a grommet from Bondi and he was shaping unreal back then as well. There were other guys – Wayne Deane from the Gold Coast, Noa Deane’s dad.”

He said that immersion in the industry, and at that time, set him up for life.

“Even when I was at G&S, the Japanese boom was starting to happen, and Peter Townend used to hang in Cronulla back in the day when he had the Bronzed Aussies surfboards,” he offers. “They were making them for the Japanese market. We were producing a hundred boards a week. We had two sanders, two polishers because all the boards were polished then with finish coats – you had to cut and buff them. We had five different shapers – people like Michael Peterson shaped there at one stage. It was full on – pretty wide-eyed stuff to see going on. I learnt to polish, then glass and sand. But, I always wanted to shape, so I’d buy seconds blanks and started shaping with these guys giving me tips. So to change to Terry Fitzgerald at Hot Buttered … that was a good stepping stone for sure.”

I ask Rasto if that gave him unfettered access to North Narrabeen – still today one of the North Shore’s most protected breaks.

“Nope, not so much,” he shakes his head with a grin. “There’s definitely a pecking order there.”

“We had five different shapers – people like Michael Peterson shaped there at one stage. It was full on – pretty wide-eyed stuff to see going on. I learnt to polish, then glass and sand.”

But Ratso did build strong friendships with people like Simon Anderson and many others that he’d see on his travels around the world to this day. Jack Reeves worked for Terry internationally. Ratso describes him as “one of the best glassers in the world”. He is based in Hawaii and Ratso found work through him in Tahiti, Europe and Japan.

“It was an unreal part of my life,” he smiles.

In 1990 Ratso came back from Australia and teamed up with the guy who had the agency for Hot Buttered. He lived in New Zealand full time and they set up a retail shop in Newmarket, which was a high-end fashion area by that time.

“It was quite expensive rent, but it went really well because it was one of the main surf shops in the city,” Ratso explains. “Things changed after quite a few years, as they do, and around 1997, 1998 it came to an end and I went in my own direction.”

Ratso left the business and went to Europe where he returned to the shaping bay for the Northern Hemisphere summer, shaping and living in Newquay, Cornwall.

“I had a good friend from here who was in the board industry there, so I ended up getting some work over there – a seasonal thing.”

It seems that wherever Ratso went he left his mark, but those places always left a mark on him, too.

“Boardriders clubs are the loose backbone of many coastal communities throughout the surfing world,” he explains. “And I’m proud to be a life member of the New Brighton Boardriders in Christchurch, where it all began for me, equally to be a life member of the Cronulla Boardriders in Sydney – the first Kiwi ever, where my professional career really started. And now to be at home in Piha, a senior member of the Keyhole Boardriders, surfing with my bros, enjoying surfing more than ever.”

Ratso moved out to Piha permanently in 1997. He started Lion Rock Surf Shop in 1999.

“So it is 21 years this year,” he laughs. “Piha’s way different now. Back then there was not the tourism that there is now. It’s gone crazy these past three or four years. It’s been busy for the shop, but the last two summers are probably the most crowded I’ve ever seen Piha in the water.”

He said Piha had become something of a creative enclave.

“You’ve got Francis Kora from Kora he’s out here and then you’ve got Neil Finn and Tim Finn – not here all the time, but they’re here. You’ve got the actress Danielle Cormack. She lives just over there and the guy that owns Huffer clothing, Steve Dunstan, he lives next door. There’s a band called System of the Down and he has a house at the top of the hill. I think there are three recording studios over the hill at Karekare. Crowded House recorded their Woodface album over there. You meet people who have lived out here and you’ve never met these guys before, it’s a really interesting place like that,” he adds.

“But the tourism has been super noticeable – especially these last three or four years. Before Christmas there’s a certain wave of people and then there’s like another group comes in after the new year – all kinds of people from Europe, Germans or French and Spanish. The downside of that is the freedom campers shitting in the bushes or on the beach and the rubbish that comes with them.”

“But, it’s good for business, too.”

He said the town’s iconic Bar broke every day, but the quality varied massively with the shifting sands.

“Last year the bank was pretty unbelievable,” he tells me. “On a low tide, you could walk past the inside rocks, which we call the Beehive, and there’s a hole through the rock where the fishermen guys walk through – the Keyhole. You could walk past the Beehive to the Keyhole and be on almost bone dry sand, which never happened.”

“The sand was so good, you could take off around past the end of the rocks, out to the next rock that’s called the Nun. And it was peeling all the way down and hugging the rocks all the way. I hadn’t seen it like that ever. The crowds were just insane.”

The announcement of the Piha Pro sent the little village into a frenzy. Pros and cons bounced around like pinballs. As the event was being built in the carpark – the scaffolding village nearly complete, Covid-19 shut the WSL and the world down. It brings a welcome pause to the peaceful Piha surf community as it looks to reset for 2021, Covid-19 permitting.

While many question the quality of the surf at Piha, Ratso has no question.

“It’s going to be interesting,” he offers. “If we’re talking about the waves from the last couple of years – the bank’s not anywhere near that at the moment. It’s definitely contestable, but the tides play a big factor here. At least with the Bar, it doesn’t matter how big it is out the back – we get a lot of big swell and it can be like eight-foot plus and messy, but it’ll break and reform. You can sit on the inside and still get reforms and you can still paddle out pretty easily, too. Even if you get caught inside, you can just do a loop and go back out with the rip. Sometimes it might not look that great from the beach, but once you get out there there’s definitely rideable waves.”

“It’s the west coast so it could be 2-6 foot any day,” he laughs. “But I think Piha is ready for an event like this. There’s been a lot of discussion and some people hadn’t been informed properly. We’re just trying to make that clearer, listen to feedback and change things. The people that are behind organising it ran the Rugby World Cup here. And they also ran the FIFA under 20s – so they’re used to big international events with a lot bigger crowds than what we’re talking about. The tough thing is that we’ve only got one road in and one road out. So that’s more of a challenge, but you just try to make it as user friendly for the local residents as possible.”

In many ways, having another year to let the idea simmer with the local community will be an advantage.

“I’d been invited to go in the World Masters Surfing Championships a couple of times,” Ratso explains. “I had never been able to go because of work commitments with Hot Buttered. Then I finally went to one in France. I approached the guy who was the head judge at that time, Perry Hatchett, and asked him about getting into judging.”

At that time Ratso had been doing some judging in New Zealand, had coached the national team and the head judge in Australia, Glen Elliot, had given him some QS’s in Australia to learn the ropes of judging.

Glen is a head judge for the International Surfing Association (ISA) and is going to be the head judge at the Tokyo 2020 – the Japan Olympics, which will be held in 2021.

“So I approached Perry in France and he gave me a go at the ASP World Juniors contest in 2000 held at Phillip Island,” Ratso recalls. “Joel Parkinson won it over Mick Fanning. I did the Newcastle WQS a month later.”

At the World Juniors event Ratso shared a room with Pritamo Ahrendt, who had himself just been catapulted into being a WCT judge.

“It’s ironic that we were both at the start of our professional judging careers, had never met before and now 20 years later he’s my boss as the WSL head judge and I’m the WSL priority head judge,” Ratso puzzles as he recollects the countless times of travelling and judging events together.

After his foray into WQS events Ratso found himself heading back to Newquay each summer – bouncing between there and Piha as the seasons dictated.

“I had an ancestry visa through my Scottish ancestry on my father’s side of the family, so I could get a work visa,” he explains. “It was renewable – it would last for five years and I renewed it three times. So I did our winter – their summer – over there and then I’d come back and do the summers here in Piha where my shop was going.”

While in Europe Ratso did more and more judging. At the time, he said it seemed like there were some conflicts at the France, Spain and Portugal contests.

“Perry basically wanted someone neutral,” he admits. “I was in the right spot at the right time. He offered for me to be the head judge over there in 2005.”

Ratso laughs at the moment.

“I was wondering if I was going to get any more judging work and then he made me the head judge,” he shakes his head. “I was quite blown out by that.”

Ratso fulfilled his head judge duties in Europe right through to 2014 and every time Europe hosted a CT event he’d judge them as well.

In early 2010 Perry moved on and Richie Porta became the head judge of the WCT. Kieren Perrow soon took over the commissioner role and shortly after the priority rulings started to bubble to the surface.

“They needed someone to do it and it was obvious that they needed a position created for it with such a change to the rules,” recalls Ratso. “They offered that role to me in 2014.”

He said the priority rules had been an evolving thing.

“There were so many things that hadn’t been in the rule book and we had to create a rule to deal with all these different situations,” he reveals. “The whole idea of priority was to make it fairer and to stop the hassling. In the CTs we just had it man-on-man and then we trialled it with three surfers and they thought, ‘Oh, that’s gonna be too hard’. But it wasn’t that bad. And we trialled it at Snapper before the event. Then they trialled it at Saquarema in Brazil at a QS with four surfers and it worked. Everyone thought it wouldn’t work. They thought it would be too much chaos for a team to follow four surfers with a camera and blah, blah, blah. But it wasn’t that bad.”

Once priority had proved itself at Saquarema it got adapted almost immediately for all QSes.

“It wasn’t compulsory in the rules, but pretty much every event did it – right down through to juniors,” recalls Ratso. “It was a game changer.”

Ratso said it has been the biggest thing since Perry Hatchett changed it to the two best waves, which he said changed the level of surfing, because everyone had to commit to big manoeuvres to get the big scores. It had been three waves before that and when Ratso used to compete, through the ’80s on the World Tour, it was four.

“And it used to be length of ride so you’d just milk a wave all the way to the beach – as much as you could grovel basically,” he admits. “Priority changes everything. You can utilise it to get the best wave of the whole heat and win. Some guys have adapted well to that and some guys, and girls, they make mistakes – sometimes minor, sometimes big – that can ultimately cost them the heat.”

“Priority changes everything. You can utilise it to get the best wave of the whole heat and win.”

“We’re one of the only sports in the world that rely on mother nature,” he concedes. “So you can sit there and wait, wait, wait, thinking a better wave is going to come whereas your competitors are surfing away and catching anything. Some guys sit too long and then you have guys like Medina and he’ll just keep paddling and catch everything – he’ll catch like 12 or 13 waves in a heat. Other guys might catch two. So there are different approaches. There are a lot of subtle things that happen with it – guys can try and block you and things like that – so it’s quite hard to police a lot of stuff.”

He said priority had cleaned up the lineup with things like stopping surfers from paddling and blocking another surfer from catching a wave.

“Then interesting things like we had at Sunset with Jack Robinson,” he shares. “He got a wave and was paddling back out and Ezekiel Lau got the wave behind and ended up where Jack was paddling back out. It was just the way the wave broke. By the time Zeke got to where he pulled into the barrel Jack just couldn’t get out of the way.”

“We get things like that and have to decide – was it intentional or not?,” he asks. “Each situation’s different. You try to get out of people’s way, but unfortunately things happen that are out of everyone’s hands. It’s mother nature.”

Also in Hawaii during the 2019 world title showdown Gabriel Medina hit the headlines for his decision to drop in on Caio Ibelli in their Round of 16 match-up. Set to his step-father booming, “burn him, burn him” in Portuguese from the beach, Medina did the math and realised he could extinguish Ibelli’s chances of scoring on that last wave. So, in the dying seconds of the heat he dropped in, burnt Ibelli and copped the interference (losing the score of his second counting wave), but knowing he had a score to win the heat. Brutal. Yes. Clever. Yes.

Ratso had a front-row seat to the drama as it unfolded.

“He’s probably the best competitor – to the rules – put it that way,” he smiles. “He’s super, super competitive and you don’t become a World Champion unless you are. Think about all the guys in the past; Andy Irons, Kelly Slater, Tommy Carroll – people like that, they’re the same. They can be as ruthless as anyone and you have to do that to win.”

He admitted that Medina was a phenomenal surfer and said things could have worked out differently if Caio had surfed that wave differently.

“But, yeah, Gabriel pushes the boundaries,” Ratso continues. “He knew mathematically he had him. He was right on the end section – he wasn’t on the main part of Pipe – it was breaking kind of funny that day. There was a lot of sand and it was more like a beachie almost.”

“He’s probably the best competitor – to the rules – put it that way,” he smiles. “He’s super, super competitive and you don’t become a World Champion unless you are. Think about all the guys in the past; Andy Irons, Kelly Slater, Tommy Carroll – people like that, they’re the same. They can be as ruthless as anyone and you have to do that to win.”

He said it was still a gamble – Ibelli could have possibly got a four and Medina’s move could have fallen into another category of unsportsmanlike behaviour, “but the judges chose not to decide that”.

“It was a very calculated decision that just blew everyone out on the beach – his team manager and everyone,” recalls Ratso. “What’s just gone on here?”

It even had Ratso double and triple checking his system.

“When things like that happen the first thing I check is what my monitor’s saying, that shows me what is on the LED lights to see if something’s displayed wrong,” he shares. “But, no, no, it’s all right. Nothing was displayed wrong. It was so obvious that Medina didn’t have priority. That highlights just how hungry he is.”

He said he met a lot of people on his role and most of them were really down to earth people.

“Like Medina, he is a good guy – he’s just a normal person and he’s always been respectful to me,” Ratso reveals. “People might hate him or like him and have serious opinions about it and him, but back in the day Slater used to do that stuff, too – and to anyone. Slater did it to Shane Beschen at the US Open of Surfing in 1996. He got an interference on him in the first minute – he literally spun around in the whitewater and got an interference on him at the start of the final. Tom Carroll – he’s ruthless, too. There are all kinds of guys who have done that stuff – whatever it takes to win. Back in the day the Aussies had this mongrel – ‘oh, fuck you, I’ll do anything to win’ attitude. Now the Brazilians have got that and look how many Brazilians are in the top 10. That speaks volumes. They’ve got that mongrel and it brings them results and, well, maybe that’s what it takes.”

“Back in the day the Aussies had this mongrel – ‘oh, fuck you, I’ll do anything to win’ attitude. Now the Brazilians have got that and look how many Brazilians are in the top 10. That speaks volumes. They’ve got that mongrel and it brings them results and, well, maybe that’s what it takes.”

“That last day at Pipe in 2019 was one of the most stressful days of surfing I’ve ever been involved in,” concedes Ratso. “It was the whole day – there were so many scenarios that could have happened. For the number one and two in the world to be on opposite sides of the draw and to meet in the final, I don’t know if that had happened before. It was an epic finish to the year for WSL, for the media and everyone tuned in. You couldn’t ask for any better.”

I ask him about the stress that comes with his role with WSL and he offers a glimpse of the casual calmness that surely serves him well in the priority seat.

“It’s not so much stressing, more just trying to get the decision right,” he offers. “It’s so crucial.”

He reflects on a ruling he had to make with Jordy Smith in Hawaii.

“Jordy was in the hunt for that world title, too – he was number three,” recalls Ratso. “The day before he paddled with his opponent and paddled enough to warrant that he did make an attempt to go for the wave. So, he lost the priority against Jesse Mendes and Jesse ended up winning the heat.”

“Obviously Jordy was pretty upset and not happy with the call, but it’s like being a referee in a football game or a rugby game – it’s a line call you’ve got to make and that’s part of the competition,” he reflects. “I just try to be fair for everyone. Sometimes I’ll ask my head judge and the senior judge if I can see some situation is going to happen. It’s a joint thing really, when the decision goes out – it’s so crucial. It has got to be right. You want to be the best and fairest you can. I lie awake at night sometimes. We watch the replays afterwards and always review our performance.”

“When the decision goes out – it’s so crucial. It has got to be right. You want to be the best and fairest you can. I lie awake at night sometimes.”

He said sometimes the judges might see something come from the commentaries team and they might have a different opinion on it.

“We don’t listen to the commentary when we’re on the job at all,” he shares. “We try to portray the right thing and sometimes that hasn’t come across as what has happened. Then we have a discussion and review all that stuff across all departments. Something might have been not quite shown the right way. Everyone can improve and learn from that.”

“It’s exciting and I love doing it.”

The WSL head judges, including Pritamo, Luiz Pereira and Ratso, sit down ahead of Hawaii and schedule the events and judging work for all the judges each year. When WSL resumes its normal operations, post Covid-19, Ratso expects to do some QS10,000s and every CT apart from the Surf Ranch where there’s no priority used because of the format. That suits Ratso.

“I’ll usually go and do something else – go surfing somewhere or have a break and come home,” he smiles. “Kelly gave us a free day at pool in 2018. We went and spent a day there – it was like nine of us judges. It was pretty cool – there’s a high level – some very good surfers.”

Ratso manages to surf most days while on tour and aims to surf twice a day when he’s home in Piha.

“On the tour we have a lot of lay days,” he explains. “In Hawaii you can only surf from eight to four in the contests so we get all afternoon and a lot of lay days to surf. They’re 12-day events and we have a house right in front of Sunset, so I just surf Sunset all the time and in Europe we get a lot of time off. I surf a lot.”

“I’m probably surfing just as much as I ever have,” he smiles. “I still ride 5’9″ and 6’0″ boards – I don’t ride longboards or anything like that.”

I nudge him and ask him if he’s considered riding a SUP.

“No way, that’s a dirty word at Piha, mate,” he barks. “I can tell you right now they’re a rare breed out here. There are a couple of guys that try it, but they’re not that welcome out here to be honest.”

Back in 2013 American company ZoSea bought the Association of Surfing Professionals and by 2015 they had transformed it into what we now know as the WSL. Since then the Americanisation of the sport has been rampant, drawn a lot of criticism and jettison many of the stalwart Australian tour legends. It has also heralded a new era for professional surfing and turned it into a mainstream sport televised to millions throughout the world. The crux of many a debate, Ratso reckons it has been the best thing for pro surfing.

“With the demise of the surf company boom that we all enjoyed through the ’80s and ’90s, this has come at the right time,” he explains. “Some of those companies are struggling now. WSL’s new direction came at the right time for the injection of the kind of money they put into the sport.”

“With the demise of the surf company boom that we all enjoyed through the ’80s and ’90s, this [WSL] has come at the right time. Some of those companies are struggling now. WSL’s new direction came at the right time for the injection of the kind of money they put into the sport.”

“The production is just phenomenal that goes out,” he adds. “There are so many people behind the scenes making it all happen. At the big events there are something like a hundred people behind the scenes. I reckon the American ownership has been really good for the sport.”

“As the ASP it was good, but it has got better with the American management,” Ratso explains. “We’ve all been paid better than we used to be from the ASP days. They’ve brought that professionalism right through and have engaged people from all walks of life. Some from the entertainment industry in America and things like that – some seriously professional people who know what they’re doing – one guy used to run ESPN Sports and Fox Sports – with people like that it’s a different world.”

He recalls one year when they were in Fiji getting invited to drinks and snacks on a yacht.

“The guy that owns Google, Larry Page, was there with his mega yacht,” he tells me. “Dirk Ziff who owns WSL, is friends with him and they took us out there for drinks and snacks in the afternoon. So we got to go on this mega yacht and it was pretty sick. It’s a whole other world. I think they had the Quiksilver guy, Mark Healey, on board as their surf coach – just cruising around.”

While Ratso is enjoying the pressure cooker that is the WSL judging team there is an event on a currently hazy horizon that he’d love to play a role at: the Olympics.

When the Olympics does take place it will be a joint effort between International Surfing Association (ISA) and WSL.

“Hats off to the ISA – they got the sport over the line to get it into the Olympics,” Ratso asserts. “That took a lot of time and rubbing shoulders with the right people. They’ve managed to do that and so congratulations to them.”

Before the Covid-19 outbreak the two organisations had held events to bring the judges together, and recently released the Olympic judging team info.

“They’re going to have two priority judges,” Ratso offers. “And I can confirm I am one of them alongside Marcel Miranda from Brazil and New Zealand’s head judge Dan Kosoof will be part of the judging team, also. It’s going to be amazing. ”

He said it was good to see that the Olympic sports were evolving to reflect what the youth were doing.

“How many more people will be able to relate to surfing?” he asks. “For me, getting a bit older, this is pretty unreal. Having the opportunity to judge at the Olympics, well, that ranks as one of the biggest achievements of my career. I’m very stoked. My sister competed in gymnastics in the Olympics and my father has been to a couple as New Zealand’s gymnastics coach, so I’m happy to do it for my family. My dad was actually at the Munich Olympics when all that terrible terrorist stuff happened.”

“Having the opportunity to judge at the Olympics, well, that ranks as one of the biggest achievements of my career. I’m very stoked. My sister competed in gymnastics in the Olympics and my father has been to a couple as New Zealand’s gymnastics coach, so I’m happy to do it for my family.”

And the achievements that Ratso has accumulated throughout his career are what put him among few others in New Zealand surfing. He’s touched so many corners of the industry and left an indelible, positive impression on them all. And, in many ways, that’s been overlooked by New Zealand surf media.

We’re guilty of it ourselves. We focus on the Maz Quinn, Paige Hareb and Ric Christie feats because they happened as we were discovering our own paths in surfing, but that shouldn’t diminish those who went before them. It was Allan Byrne and then Ratso who first forged the path to Australia and Hawaii and the world.

In Ratso’s competitive surfing era they had the World Tour – the Top 16 in the world as decided through the trials events, which were held separately.

“To get through the trials we used to have 200-odd competitors,” remembers Ratso. “So you’d have to go through four, five or six rounds just to get through.”

He did just that from 1983 to 1987 – five years straight.

“When I first started in 1983 I travelled with Occy – he was 16,” he recalls. “His mum is a Kiwi. I remember we went to California and he got some boards off Rusty and it was phenomenal to see in those couple of months just how much his surfing changed. It was because of those boards – he improved so much, so fast. It was quite noticeable. He was 17, doing really well at Pipe and he just went to another level so quick.”

That era was defined as much for its explosive power surfing as it was for its party culture. Ratso said that party element wasn’t the same these days.

“The surfers can make quite good money,” he explains. “They train a lot and they have coaches, nutritionists and managers – it has become a lot more professional. Social media has changed a lot of that, too. I mean it’s so easy to get caught out if you’re doing the wrong thing. If you’re out drinking and partying when you’re not supposed to be, it’s not a good look.”

“Surfing has become a lot more professional. Social media has changed a lot of that, too. I mean it’s so easy to get caught out if you’re doing the wrong thing. If you’re out drinking and partying when you’re not supposed to be, it’s not a good look.”

I joke with him that the judges can still sneak off for a few quiets.

“No way,” he states emphatically. “You know what it’s like, mate, we sit in a tower for eight to 10 hours a day and you go home and have some dinner and you’re pretty much in bed by eight o’clock. That’s the truth, I swear. You’re mentally drained.”

“After Pipe finished last year, I was just so happy it was over,” Ratso confides in me with tears welling in his eyes as he revisits the emotional loading. “I got home and Sunset was pumping and I was just so tired. I just sat down and I was just like, ‘whew, that’s over’. It was quite emotional for me. I mean it was good – nothing went wrong. It was the biggest day of the year – the title race came down to that one day. If there was some sort of fuck up, that’s what you’d be remembered for. It’s emotionally draining, but I love it.”

“We sit in a tower for eight to 10 hours a day and you go home and have some dinner and you’re pretty much in bed by eight o’clock. That’s the truth, I swear. You’re mentally drained. If there was some sort of fuck up, that’s what you’d be remembered for. It’s emotionally draining, but I love it.”

From the Cooly Kids to the Brazilian Invasion of the world tour, Ratso has witnessed the ebb and flow of nations dominating the sport. He thinks New Zealand’s best show of force has already been.

“When we had Daniel Kereopa, Maz Quinn, Chrissy Malone, Blair Stewart and that whole posse of guys – that was I think the strongest years of our surfing,” he concedes. “They came through the ranks from cadets, to juniors then into the open events. What people may not always remember is how well Kereopa was doing overseas. When Maz was starting to hit his straps Kereopa was still getting into the quarterfinals in those 6000 events – he was a seriously good surfer. And then Jay Quinn came along and Bobby Hansen – that was a great era. Then there was a big gap before Billy Stairmand and Ricardo Christie came along.”

He said Kehu Butler and Elliot Paerata-Reid were the next wave.

“Elliot’s a great surfer in waves of consequence,” he notes. “He surfs heavy reefbreaks really well.”

Ratso said there had been big moments like when Maz won the Australasian Junior title, which Kehu then went on to win in 2018, and when Arini Mason won the girls Australasian Junior title – that people didn’t fully understand.

“To beat all the very best in Australia … and in their own country? That’s super hard,” he tells me. “That’s a huge achievement to beat all the best in Australia when you’re a Kiwi. Arini’s little sister, Sarah, she made the CT – she was on the tour and a great surfer, too.”

“Paige deserves massive credit here, also,” he adds. “She won Margaret River – do people remember that? To requalify so many times for the CT is a phenomenal achievement. She has raised the bar for all women surfers in New Zealand. If you have a dream and you really want it, you can achieve anything.”

“Then you have Ella Williams – a total darkhorse in the 2013 ISA World Juniors, but she surfs strongly to the final and takes out the much fancied Tatiana Weston-Webb, to claim a world title for New Zealand.”

While he said there would certainly be someone else coming along, he said that the modern sport of surfing had a very large financial barrier to entry.

“The reality now is that it takes money,” Ratso admits. “All the industry has moved back to Australia – to get that backing from an Australian company is going to be harder than ever, because you’re fighting against the Australians as well. And it’s very hard for Kiwis to get any sponsorship out of our New Zealand companies.”

“The reality now is that it takes money. All the industry has moved back to Australia – to get that backing from an Australian company is going to be harder than ever, because you’re fighting against the Australians as well. And it’s very hard for Kiwis to get any sponsorship out of our New Zealand companies.”

There were some who had set themselves up for success and he points to Kehu.

“He’s got some good backing and he’s grown a bit – he’s not a kid anymore,” Ratso tells me. “He’s grown up, he’s tall and solid and he has his head screwed on the right way.”

He said another good example of the mental fortitude required was Aussie surfer Wade Carmichael.

“He tried for years to get on tour,” he continues. “He was always the top junior in Australia, but then he got dropped by Rip Curl and he was just grovelling. He kept plugging away, plugging away – you can tell the guys who have the ability to make it. Another one is Juan Duru from France – many years plugging away and then he finally made it. That’s why they make it so just the top 10 come out of the QS – they have to be up to that level. Those two examples have both proved that if you keep plugging away and believing in yourself then you can do it.”

That brings us to the question of our long-running WQS battler Billy Stairmand, who was surfing better than ever as we went into the Covid-19 holding pattern.

“I think he’s got the ability,” admits Ratso. “It just takes a bit of bit of luck sometimes – a bit of a run of luck and he could string it together. He definitely had a good 2019. He’s got some more backing and he has good boards with Sharp Eye – he’s a good shaper and Billy seems to have a new zest for life. That helps.”

Tapping into that zest for life seems to come naturally each summer when Ratso returns to a house he recently bought with his girlfriend in Piha’s bushclad hills.

“Look at the view, bro,” he smiles. “There’s nowhere like it in the world. When you come over the top of the hill, it’s like, ‘wow’. It’s like that every time I come home. I don’t want to leave. People come from all around the world to come and see this. So it’s good to be here and call this home and to have my shop, too. I’m lucky to have that, because once it’s all over, this is what I have. I’ll be here with my shop. It’s not a bad spot to be.”

“Touch wood,” he says reaching for the table. “I’ve got a few more years in it with the WSL. I’m very happy getting paid to do what I am doing. And I surf just as much as I can. You ask any of the boys out here, I’m pretty much the biggest grommet out here.”

Back in his garage he shows me three boards he’s just finished making – part of his “2020 collection”. There’s a swallow tail, a squash tail and his step-up is a rounded pin. They each have a blue diamond featuring a rat and the word Ratso. Below that a dragon breathes fire with the words “International Bastards” in the flames.

A teary Ratso turns to me.

“One thing I wanted to say is that firstly there was Allan Byrne,” he explains. “He paved the way for a lot of us guys. Then I did it and then Maz and then Ricardo. I’ve read a lot of articles where they talk about Ricardo being the second ever male surfer to qualify on the World Tour after Maz, and that Maz was the first guy to go on the World Tour. That isn’t true. Byrnesy was the first, I definitely was the second, and then Maz. They forgot about Allan Byrne and me … and that’s the truth.”

Ratso elaborates about the 1981 Pipeline Masters competition that would have to rate as one of New Zealand’s greatest ever sporting moments. New Zealand’s own “Bustin’ Down The Door” juncture.

“A lot of shit happened over there,” Ratso explains. “Buttons dropped in and got an interference in the semi-final and, the story I heard, is that they hassled the judges claiming that Buttons had to be in the final. And so they made a seven-man final. Byrnesy had to surf in that seven-man final and Buttons got another interference in it.”

Al went on to battle head-to-head with Australian Simon Anderson in the final. It was a thrilling final that eventually went Simon’s way, surprisingly to Al Byrne’s relief – he didn’t feel it would be a good look for this Kiwi surfer to take such a prestigious title. Simon later described Al as being “the most impressive surf in that ’81 Pipe final”.

“Byrnesy paved the way for all of us,” echoes Ratso.

“I’ve read a lot of articles where they talk about Ricardo being the second ever male surfer to qualify on the World Tour after Maz, and that Maz was the first guy to go on the World Tour. That isn’t true. Byrnesy was the first, I definitely was the second, and then Maz. They forgot about Allan Byrne and me … and that’s the truth. Byrnesy paved the way for all of us.”

And while his world tour years didn’t bring him a word title, Ratso never gave up the dream. In 2011, at the ASP World Masters Championships in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, he had a moment of his own.

“I was invited to go to the Masters and then I ended up winning it and beating Rabbit (Wayne Bartholomew) in the final,” he recalls. “That was pretty much one of the highlights of my life. Rabbit and I are good mates, but he’s the same – he’s probably one of the original ruthless competitors – he’s the same level as Medina – he would do anything to win and good on him.”

The tight final saw Ratso displace the then reigning Grand Masters Champion and former World Champion for the win.

In winning that event Ratso became the first Kiwi ever to win an ASP World Title.

“It was so hard being a Kiwi – often competing in Australia and losing a lot of three-two split decisions,” he offers. “So to finally beat those guys, it was good and to win a World Title that was great.”

I ask Ratso if he thinks New Zealand does enough to support its athletes.

“You see surfing so much on TV these days,” he begins. “It could be any kind of ad and they’ll have a surfing background – a picture or something of surfing – even random things like banking or a furniture ad, or something. All these people do it in the mainstream now.”

He said surfing had grown and when Ricardo was doing well at Pipeline, Hawaii in 2019, half the country would have been watching – they were national names now.

“We all pretty much live around the coast somewhere and we’ve got great waves and it’s kind of amazing that we don’t have a few more at a high level, really,” he adds. “It comes down to the population size – like in Australia – they’re so competitive – your average guy in the pub can surf pretty good. But I’m sure there’s going to be someone else eventually.”

“If I’ve come from the waves I surfed at Waimairi Beach to now, then anyone can do it,” he smiles. “If you believe in yourself, you can do it … anyone can. There are ups and downs – it’s life – you have relationships, money – it comes and goes, but if you’ve got the passion, you can make it.”

“But you have to always remember the reason why any of us started surfing. It was because it was super fun – a fun thing to do with your mates,” Ratso offers. “It’s not all about contests, or being a competitor – it’s about getting that buzz – going out in any surf conditions and having fun no matter what level of surfer you are.”

“But you have to always remember the reason why any of us started surfing. It was because it was super fun – a fun thing to do with your mates. It’s not all about contests, or being a competitor – it’s about getting that buzz – going out in any surf conditions and having fun no matter what level of surfer you are.”