Monster waves in the Southern Ocean could grow even bigger and more frequent under climate change, scientists warn. Science journalist Jamie Morton explains what’s going on in the southern latitudes storm engine.

Extreme waves in the wild and windswept ocean below New Zealand, stretching across notorious latitudes dubbed the “roaring 40s”, “furious 50s” and “screaming 60s”, already pose big risks to ships.

When the HMNZS Otago met some stretching more than 20m high in 2017, the 1900-tonne offshore patrol vessel came close to capsizing, with 75 people on board.

That same swell, itself a record at 19.4m, turned reefs around Dunedin into big wave focal points. Peaking in the early morning the swell provided a six-hour wave window for the local tow crews.

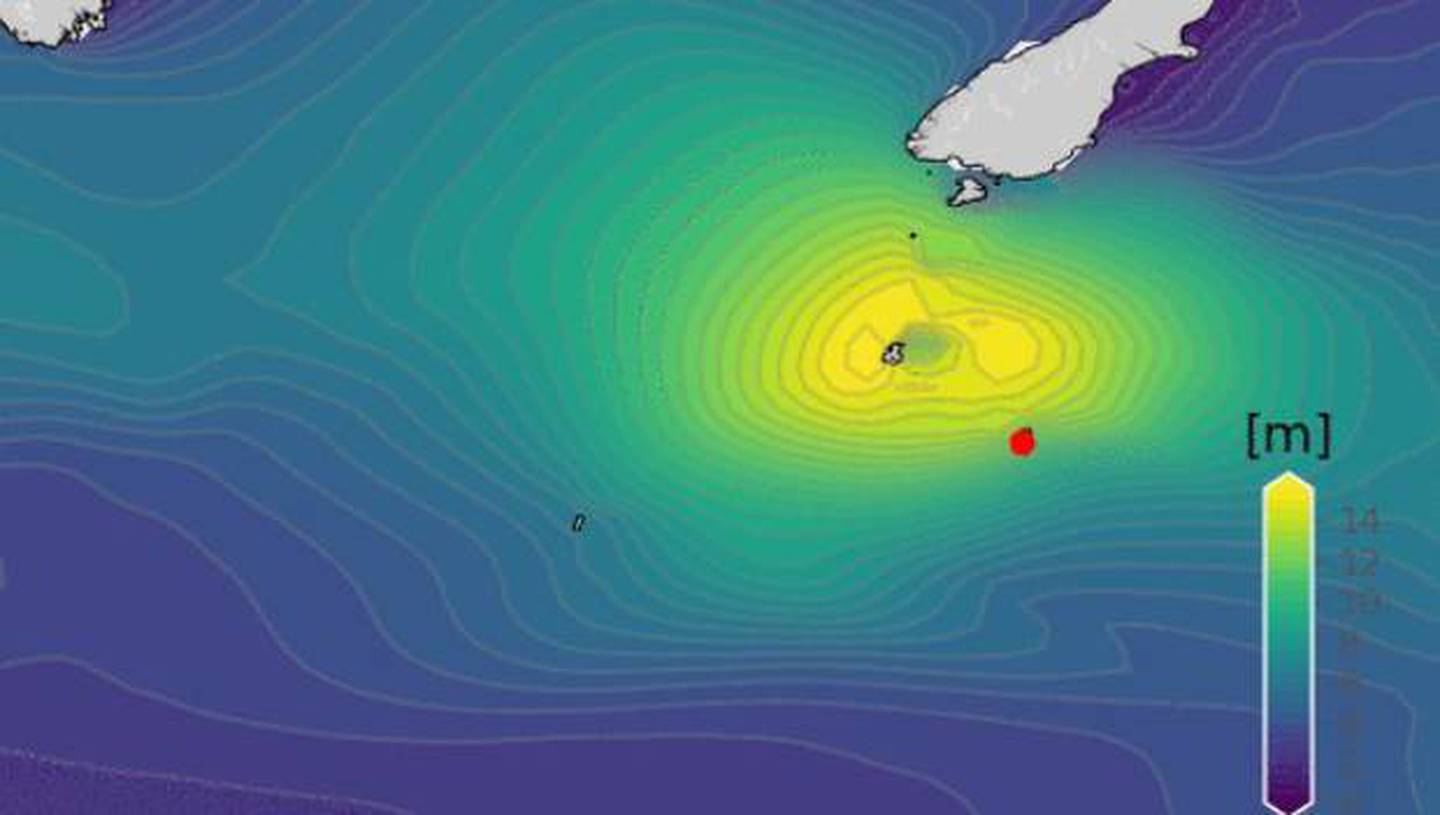

The following year, the largest wave ever recorded in the Southern Hemisphere – a 23.8m giant that formed in the thick of a huge, deep storm – was measured by a buoy moored off Campbell Island.

It smacked full force into the Catlins and created one of the biggest waves to ever be ridden in New Zealand.

During the depths of winter, these waves are enormous, averaging more than 5m, regularly exceeding 10m, and sometimes likely reaching more than 25m.

Anything more than 20m high is highly hazardous to vessels. Waves that climbed to 14m forced the HMNZS Wellington to turn around part-way to the Subantarctic islands in 2014.

Ships tend to negotiate heavy seas by sailing head-on into the direction the waves are coming from, but, fortunately, there’s little shipping traffic in the ocean. What vessels are operating range from icebreakers and research boats to fishing vessels and small cruise liners.

One recent study found that extreme waves in the ocean had grown by 30cm – or 5 per cent – in just the past three decades, all while the region had grown stormier, and even gustier, with extreme winds strengthening by 1.5m a second.

Now, a new study has found that a warming planet will cause stronger storm winds triggering larger and more frequent extreme waves over the next 80 years – with the largest increases occurring in the Southern Ocean.

The University of Melbourne researchers simulated Earth’s changing climate under different wind conditions, recreating thousands of simulated storms to evaluate the magnitude and frequency of extreme events. The study found that if global emissions are not curbed there will be an increase of up to 10 per cent in the frequency and magnitude of extreme waves in extensive ocean regions.

In contrast, it found there would be a significantly lower increase where effective steps are taken to reduce emissions and dependence on fossil fuels.

In both scenarios, the largest increase in magnitude and frequency of extreme waves was in the Southern Ocean.

They found the magnitude of a one-in 100-year significant wave height event increased by five to 15 per cent over the ocean by the century, compared to the 1979 to 2005 period.

The North Atlantic, meanwhile, showed a decrease of five to 15 per cent at low to mid latitudes, but an increase at high latitudes of around 10 per cent.

The extreme significant wave height in the North Pacific increased at high latitudes by five to 10 per cent.

One of the paper’s authors, Professor Ian Young, warned that more storms and extreme waves would come with rising sea levels and damage to infrastructure.

“Around 290 million people across the world already live in regions where there is a one per cent probability of flood every year,” Young said.

“An increase in the risk of extreme wave events may be catastrophic, as larger and more frequent storms will cause more flooding and coastline erosion.”

Lead researcher Alberto Meucci said the study showed that the Southern Ocean region is significantly more prone to extreme wave increases with potential impact to Australian, Pacific and South American coastlines by the end of 21st century.

“The results we have seen present another strong case for reduction of emissions through transition to clean energy if we want to reduce the severity of damage to global coastlines.”

The research comes as New Zealand scientists have been getting a much clearer picture of the Southern Ocean’s extremes with wave buoys deployed by science-based consultancy MetOcean Solutions.

The ocean currently sucks up more than 40 per cent of the carbon dioxide we produce, acting as a temporary climate-change buffer by slowing down the accumulation of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere.

Yet the same westerly winds that play a critical role in regulating its storing capacity are now threatening its future as a CO2 bank, by bringing deep carbon-rich waters up to the surface.

Many climate models have already predicted that the westerly winds overlying the ocean would get stronger if atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations continued to rise.

Niwa marine physicist Dr Craig Stevens said the new findings had important implications for how we in New Zealand viewed our coastal ocean over the coming century.

“Being a very maritime nation, a lot of our infrastructure, and way of life, is connected to and influenced by the ocean around us,” he said. “So advanced awareness for planning authorities, and the processes to take the information seriously, is vital.”

Stevens said there would be some impacts from these changes over the coming decades that are difficult to forecast – especially around how coastal ecosystems and cultural values respond.

“The waves and changing sea level will affect coastal sediment and erosion patterns as well as wave exposure for marine plants and animals living along these coasts,” he said. “Also there are some feedback loops where a changed wave climate will affect heat and CO2 transfer.”

It was also known, he added, models and observations didn’t always match – especially around extreme events.

“So we certainly need more data to clarify these sorts of predictions. This is especially true over the Southern Ocean where very large waves build up and so extreme conditions are frequently possible,” he said. “It is definitely motivation to gather more data in the Southern Ocean, where most of the heat captured by the planet is stored, on a range of climate processes and better understand how they affect all of us in Aotearoa New Zealand.”